Last Wednesday, September 23rd, the Department of Labor & Industries

formally announced its proposed rate increase for the state’s workers’

compensation system for 2016.

Overall, the proposed

rate increase is 2 percent, which constitutes a system-wide average. Some

of the risk classes that comprise the State Fund would receive a higher

increase, some lower.

The rate proposal is up from the 1.1 percent in additional premium income

the Department forecasts it will need to pay benefits and administration in

2016. The difference is meant to assist with recovery of the State Funds’

reserves covering disability benefits and pensions.

The announcement drew fire from

the Association of Washington Business as an unnecessary increase. Echoing that

theme, former Attorney General and public policy commentator Rob McKenna wrote

that the rate increase amounts to “tak[ing] more money than is necessary

out of Washington businesses [to] park it in Olympia,” showing the need for

further workers’ comp reforms. Both statements noted that Oregon, by contrast,

intends to drop rates by more than 5 percent next year. The state AFL-CIO,

meanwhile, generally

praised the announcement as modest and reasonable.

So what to make of L&I’s rate proposal?

The process

At the outset, while there are many notable peculiarities about L&I’s

rate setting process (e.g., a monopoly state; premiums by worker hour rather

than payroll; in-house versus by rating bureau), there are two big picture

concepts to keep in mind.

First, the Department calculates an overall rate that is comprised of

premiums for the three major (and a few very minor) funds – the Accident

Fund, which primarily covers wage replacement for temporary and permanent disability,

the Medical Aid Fund, which primarily covers health care for injured workers,

and the Supplemental Pension Fund, which covers annual cost of living

adjustments (COLAs) for people receiving wage replacement benefits.

Self-insured employers do not pay premiums into the Accident and Medical Aid

fund but do pay premiums, by way of an assessment, for the Supplemental Pension

Fund. State Fund employers can (in theory, must) recoup half the Medical Aid

premium cost from workers by way of a payroll deduction.

Secondly, the Department’s actuaries calculate an “indicated” or

“break-even” rate for the following year based on a forecast of what revenue

will be needed to break even on anticipated claim and administrative costs.

Taking into account the indicated rate, the health of the Department’s

insurance reserves, and a variety of external factors – various economic

indicators, potential response by major stakeholders of the system, and so on –

L&I issues a “proposed” rate that is sometimes higher, sometimes lower, and

sometimes exactly the indicated rate.

Since the State Fund is a non-profit entity, if the proposed rate is higher

than the indicated rate, it signals an effort to build contingency reserves in

one of more of the funds. If it is lower than the indicated rate, it signals an

effort to use reserves to effectively buy down the rate, either to control

reserve levels, or provide rate relief — for instance in a down economy.

The “proposed rate” goes out for public hearing each October and, absent a

significant hue and cry from the public, or some change in economic

circumstances, typically becomes the “adopted” rate in December and goes into

effect January 1 of the following year.

Recently, L&I has added new messaging to its rate setting. The

Department has always talked about stable and predictable rates and reserve

maintenance as its touchstones, but now states that it benchmarks its rate

increases against wage inflation.

It’s not so much that wage inflation necessarily drives the rate up or down,

as we’ll see below, but rather inflation is proposed as an economic indicator

of the reasonableness of the rate increase, that it equals or beats a given

year’s wage inflation. Relatedly, L&I contends that insurers in the other

49 states who charge premium by percentage of payroll see revenue increases in

times of wage inflation without increasing rates – that the effective increase

is hidden in the wage inflation, whereas L&I must be transparent about the

markup it is taking.

The proposal

The overall proposed increase is 2 percent, off a “break-even” indication

of 1.1 percent. But the story by fund is more interesting.

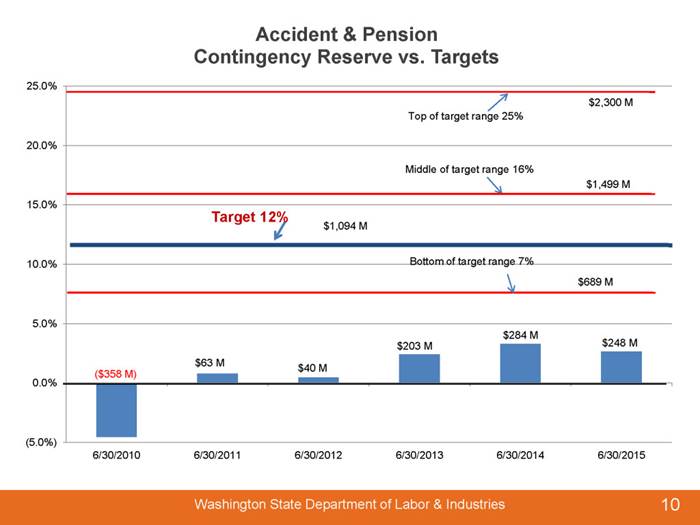

The Accident Fund

In the Accident Fund, which remember, covers the cash disability benefits (time loss and pensions), the Department is actually looking at a -4.3 percent break-even indication for 2016. This is good news, because it implies reduced frequency and severity of injuries and better return to work outcomes for workers. But L&I has proposed a 2.6 percent increase for the Accident Fund, a swing of nearly 7 percent.

Where’s that money going? By and large into the Accident Fund contingency reserve. The Accident Fund contingency reserve presently stands at about $248 million. In a $12 billion system, that’s not much. In fact, the Department’s target for the Accident Fund reserve is approximately $1.1 billion, so current levels are well below target.

One reason for that is Washington’s notoriously high time loss benefits, average time loss duration, and pension frequency. Washington’s time loss benefits are more generous than most states in amount and duration; our average workers’ lost days are more than twice the national average; and the number of lifetime pensions awarded annually in Washington is the highest in the nation by orders of magnitude. All of that impacts the Accident Fund, which was hit by declining premiums throughout the great recession, and has never recovered.

The Pension Discount Rate

Also complicating the Accident Fund picture – and of direct interest to self-insured employers – is the Department’s Pension Discount Rate. This is the percentage the Department uses to discount its long-term investments to cover pension costs to present dollars, taking into account the time value of money. It’s supposed to be a realistic reflection of L&I’s actual return on investments – otherwise L&I is overstating the value of its reserves.

For decades the discount rate has been at 6.5 percent. The Department wants to set it at 4.5 percent, step by step, over time. But for every tenth of a percent the discount rate drops, the Accident Fund reserve drops by $30-$50 million. So just half a percentage point reduction in the Department’s accounting could wipe the whole Accident Fund contingency reserve entirely. This is kind of scary, since L&I’s actuaries think it should be two whole points (or more!) lower in order to align with their investment expectations.

Furthermore, self-insured employers must reserve cash or cash-equivalents for their workers’ pensions according to Department formulas employing the discount rate. When the Department steps down the discount rate, self-insured employers have to make up the difference in value of their pension reserves right away – in cash.

So the Accident Fund is historically volatile, and you can see where a -4.3 percent break even for 2016 – ordinarily, a harbinger of good news – has instead turned into a proposed 2.6 percent increase for the state’s employers.

By the way, how was year-over-year wage inflation – the Department’s rate-setting benchmark — 4.2 percent but the Accident Fund, which pays for lost wages, breaks even at -4.3 percent? Good question. It just shows that wage inflation evidently isn’t being benchmarked as an insurance cost driver, but as an external economic indicator to compare against.

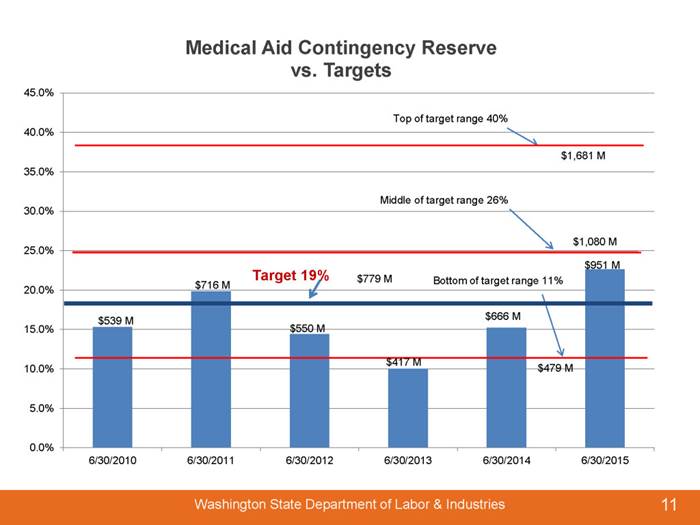

The Medical Aid Fund

In contrast to the Accident Fund, the Medical Aid Fund is generally healthy. Its contingency reserve sits at approximately $951 million, above L&I’s current target of $779 million. Health care in Washington workers’ comp is governed by a fee schedule, a closed formulary for prescriptions, tightly managed treatment guidelines and coverage decisions, utilization review, and is generally much less litigious than the cash disability benefits side of the system. Primary cost drivers here include excessive utilization and year-over-year medical inflation.

[See first chart below]

Again in contrast to the Accident Fund, to break even next year in the Medical Aid fund, L&I forecasts an 8.1 percent increase in cost. Yet the Department has proposed no rate increase, carrying the 2015 rate over.

Three things are likely at play with that decision. First, the Medical Aid Fund can afford it insofar as it is over-target on its contingency reserve. Second, it helps the math insofar as it allows L&I to increase the Accident Fund rate 7 percent over break even and still arrive at just a 2 percent overall increase. Third, the Medical Aid Fund premium is expected to be paid half by workers of State Fund employers through a payroll deduction; and so it engenders the specific scrutiny of the labor unions who have historically opposed, with varying levels of force, increases in this fund’s premiums.

The Supplemental Pension Fund

The Supplemental Pension Fund pays for cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) for workers receiving time loss or pension payments based on year-over-year wage inflation. It doesn’t have a contingency reserve; it is pay-as-you-go, with each year’s premium assessment meant to cover that year’s anticipated COLA. Self-insured employers pay the Supplemental Pension Fund assessment along with State Fund employers. Half of this premium can be deducted from worker pay as well.

For 2016, the Supplemental Pension Fund breaks even at a 9.8 percent increase. The Department has proposed a 6.25 percent increase. But wasn’t wage inflation 4.2 percent? Huh?

Follow us down the rabbit’s hole for a moment.

In 2011, as part of that year’s compendium of workers’ comp system reforms, and purely as a cost-savings measure, the Legislature froze COLAs for that year, with no “catch up” in future years. At the time, the Department estimated $30 million in annual savings in 2012, up to $40 million by 2017.

Enter the claimants’ bar. Creatively exploiting arguably poor draftsmanship on the Legislature’s part, litigation arose advancing the theory that the Legislature intended in 2011 that workers receiving the maximum allowable time loss payment continue to receive a COLA, while all remaining workers did not. Surprisingly (or not), our Court of Appeals accepted this absurd view of legislative intent, and the Supreme Court allowed the decision to stand.

So the case of Crabb v. Labor & Industries, standing for the unlikely notion that the workers receiving the highest possible time loss payment and only those workers would receive a COLA for 2011 built into the following years, to the exclusion of all other workers receiving lower benefits, is costing the Department about $28 million in back payments and $7 million per year in increased costs, severely undercutting the Legislature’s intent to save money by freezing COLAs.

So if there were no Crabb decision, the break-even for the fund would be 2.5 percent. With the Crabb effect, the $35 million in extra payments attributable solely to that case result in a 9.8 percent break even. The Department is proposing to spread that increase out over two years, and so has proposed only a 6.25 percent increase.

What are other states doing next year with workers’ comp rates?

So, taking the three major funds together, we have a proposed overall average increase of 2 percent for 2016. How does this compare around the country?

Early critics of the rate announcement have pointed out Oregon’s announced 5.3 percent premium decrease next year, renewing the frequent lament – why can’t our system be more like Oregon’s? Indeed, just today, it was further announced that Oregon’s version of a state fund is returning $120 million back to employers next month in the form of dividends.

Looking around the country, it would appear that Oregon’s experience is mainstream, and our state’s proposed increase, while not the highest, is an outlier.

The National Council of Compensation Insurance (NCCI) serves as a rating and filing bureau for 37 states and the District of Columbia.

From NCCI’s filings, you see that of the 38 jurisdictions, 31 are decreasing rates next year. Only seven are increasing, ranging from 0.4 percent in the District of Columbia to 3.4 percent in Virginia.

[See second chart below]

A cynic might ask, is there no wage inflation in any of those 31 states (and Oregon)?

Now, state to state workers’ comp comparisons are intrinsically apples-to-oranges, especially with rates. Washington charges by the hour; everybody else charges by payroll. Washington does attempt to convert its rates to a payroll basis, both to submit to the biennial Oregon Premium Rate Study, and to try to show that on a payroll basis, its rate increases are actually decreases. But few understand how L&I states payroll data when it only collects hourly data, and as such, many remain skeptical of this claim, just as they remain skeptical of the Department’s (recently sinking) ranking in the Oregon study. L&I could be more transparent, to be sure, about showing its work when it makes payroll basis claims in an hourly basis state.

Nevertheless, in the big picture, it is interesting to see that most of the country’s competitive workers’ compensation systems are in a rate decrease cycle presently, whereas Washington is set in a cycle of moderate but steady increases to account for operations and to build reserves.

A good question for the Department as it heads into public hearings on its rate filing next month would be, why is our system so seemingly counter-cyclical?

And a good question for large State Fund employers who have the wherewithal to operate their own workers’ comp programs, is it a good time to consider self-insurance?